Battle of Salamis (480 BC)

Prelude

The Allied fleet now rowed from Artemisium to Salamis to assist with the final evacuation of Athens. En route Themistocles left inscriptions addressed to the Ionian Greek crews of the Persian fleet on all springs of water that they might stop at, asking them to defect to the Allied cause. Following Thermopylae, the Persian army proceeded to burn and sack the Boeotian cities that had not surrendered, Plataea and Thespiae, before marching on the now evacuated city of Athens. The Allies (mostly Peloponnesian) prepared to defend the Isthmus of Corinth, demolishing the single road that led through it, and building a wall across it.

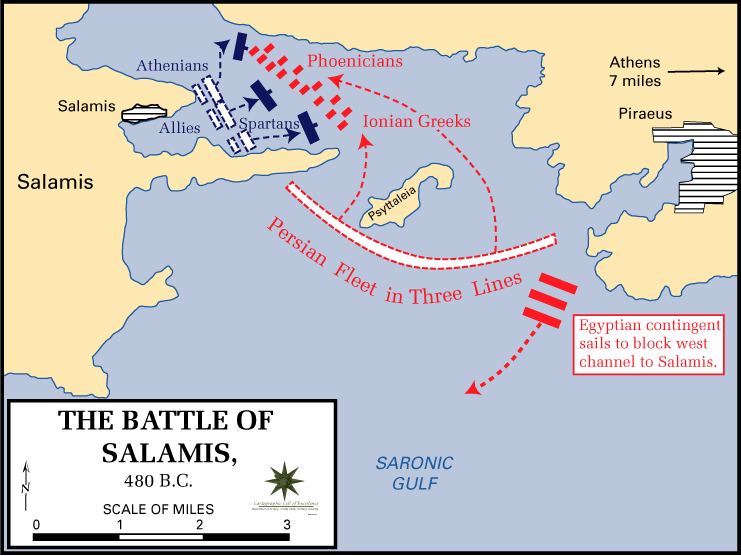

This strategy was flawed, however, unless the Allied fleet was able to prevent the Persian fleet from transporting troops across the Saronic Gulf. In a council-of-war called once the evacuation of Athens was complete, the Corinthian naval commander Adeimantus argued that the fleet should assemble off the coast of the Isthmus in order to achieve such a blockade. However, Themistocles argued in favour of an offensive strategy, aimed at decisively destroying the Persians' naval superiority. He drew on the lessons of Artemisium, pointing out that "battle in close conditions works to our advantage". He eventually won through, and the Allied navy remained off the coast of Salamis.

The time-line for Salamis is difficult to establish with any certainty. Herodotus presents the battle as though it occurred directly after the capture of Athens, but nowhere explicitly states as much. If Thermopylae/Artemisium occurred in September, then this may be the case, but it is probably more likely that the Persians spent two or three weeks capturing Athens, refitting the fleet, and resupplying. Clearly though, at some point after capturing Athens, Xerxes held a council of war with the Persian fleet; Herodotus says this occurred at Phalerum. Artemisia, queen of Halicarnassus and commander of its naval squadron in Xerxes's fleet, tried to convince him to wait for the Allies to surrender believing that battle in the straits of Salamis was an unnecessary risk. Nevertheless, Xerxes and his chief advisor Mardonius pressed for an attack.

It is difficult to explain exactly what eventually brought about the battle, assuming that neither side simply attacked without forethought. Clearly though, at some point just before the battle, new information began to reach Xerxes of rifts in the allied command; the Peloponnesians wished to evacuate from Salamis while they still could. This alleged rift amongst the Allies may have simply been a ruse, in order to lure the Persians to battle. Alternatively, this change in attitude amongst the Allies (who had waited patiently off the coast of Salamis for at least a week while Athens was captured) may have been in response to Persian offensive maneuvers. Possibly, a Persian army had been sent to march against the Isthmus in order to test the nerve of the fleet.

Either way, when Xerxes received this news, he ordered his fleet to go out on patrol off the coast Salamis, blocking the southern exit. Then, at dusk, he ordered them to withdraw, possibly in order to tempt the Allies into a hasty evacuation. That evening Themistocles now attempted what appears to have been a spectacularly successful use of disinformation. He sent a servant, Sicinnus, to Xerxes, with a message proclaiming that Themistocles was "on the king's side and prefers that your affairs prevail, not the Hellenes". Themistocles claimed that the Allied command was in-fighting, that the Peloponnesians were planning to evacuate that very night, and that to gain victory all the Persians need to do was to block the straits. In performing this subterfuge, Themistocles seems to have been trying to bring about exactly the opposite; to lure the Persian fleet into the Straits. This was exactly the kind of news that Xerxes wanted to hear; that the Athenians might be willing to submit to him, and that he would be able to destroy the rest of the Allied fleet. Xerxes evidently took the bait, and the Persian fleet was sent out that evening to effect this block. Xerxes ordered a throne to be set up on the slopes of Mount Aigaleo (overlooking the straits), in order to watch the battle from a clear vantage point, and so as to record the names of commanders who performed particularly well.

According to Herodotus, the Allies spent the evening heatedly debating their course of action. The Peloponnesians were in favour of evacuating, and at this point Themistocles attempted his ruse with Xerxes. It was only when Aristides, the exiled Athenian general arrived that night, followed by some deserters from the Persians, with news of the deployment of the Persian fleet, that the Peloponnesians accepted that they could not escape, and so would fight.

However, Peloponnesians may have been party to Themistocles's stratagem, so serenely did they accept that they would now have to fight at Salamis. The Allied navy was thus able to prepare properly for battle the forthcoming day, whilst the Persians spent the night fruitlessly at sea, searching for the alleged Greek evacuation. The next morning, the Persians rowed into the straits to attack the Greek fleet; it is not clear when, why or how this decision was made, but it is clear that they did take the battle to the Allies.

HISTORY

RESOURCES

This article uses material from the Wikipedia article "Battle of Salamis", which is released under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share-Alike License 3.0.

© Stories Preschool. All Rights Reserved.